#5 - Conversations

#5 - Conversations

THE PAINTING

Rowan Williams, Looking East in Winter (2021), page 19 - And as a result of Adam’s divided perception, the introduction into human awareness of the perception of the world as symbolic only of the self’s imagined needs, we need restoration. Habituated to this false awareness of the world, we have become forgetful of our nature and have to be awakened and to keep awake; as Mark the Ascetic observes (On the Spiritual Law #61–2, I, p. 114), forgetfulness is a form of ontological deficiency, a step towards self-destruction, a state of mind that is not only absorbed in unreal objects but is itself a shadow existence. Forgetting your nature is death; awareness is the condition for life. When Christ’s gracious action has opened the way to ‘natural understanding’ (Mark, Letter to Nicolas the Solitary, I, p. 149), the dual habits of contrition and gratitude keep before us the nature we had almost lost and preserve us from defeat by the passion of lust and anger, which – to use an awkward but helpful phrasing – de-realize other things and persons, making them either objects for possession and manipulation or objects of hatred and fear.

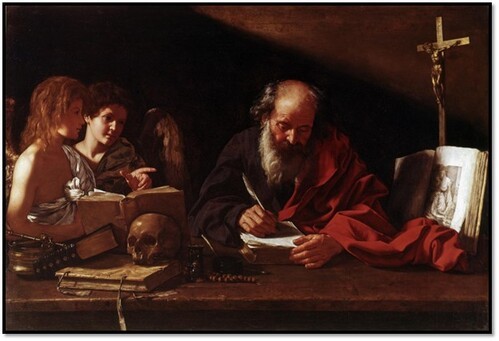

Let us look at the painting.

Because we see St. Jerome,3 that remarkable, complicated man, working in his study at the center of this painting, we might conclude that he is the subject4 of this painting. “Oh yes, that painting is about St. Jerome, one of the four great Doctors of the Latin Church.”5

But here is the problem with this conviction. A genuinely holy person would never say that his or her life and work, or any painting with him or her prominently featured in it, was about him or her. It could not be so; it must not be.

The holier a person is the more he or she knows, and therefore insists, “I am nothing. But the God I love, and the works of my life, are about God, the Trinity of Persons. Please don’t break my heart by praising me; but join me in praising God through Whom I have had my life. But it would mean a lot to me if you were to love me and to know that God sent me.” In many places in the Gospels, we notice how clearly Jesus, “the holy One of God”, understood this about Himself, as for example:

John 14 (NJB):

Therefore, St. Jerome would be relieved, and grateful, if you insisted that this painting is about other things than him. Could it be about the (divine) light that streams in from the left, illuminating his mind (notice how brightly his head/his intellect is shining), and which allows us to see this scene at all? Or could it be about those two Angels who have come to read along with him the Scriptures? (For heaven’s sake you couldn’t say the painting is about him when two beautiful Angels are right there!)

Notice how his Bible is open over there to his left, which stands under (i.e., “to understand”) the greatest Sign of his Lord, the Crucifix – the whole Scripture to be interpreted through the reality of that severe7 Beauty. Notice also how the Angels have laid open their Bible to the same pages, giving learned suggestions to St. Jerome as he works trying to decide how best to interpret a particular biblical passage.

But here is the problem with this conviction. A genuinely holy person would never say that his or her life and work, or any painting with him or her prominently featured in it, was about him or her. It could not be so; it must not be.

The holier a person is the more he or she knows, and therefore insists, “I am nothing. But the God I love, and the works of my life, are about God, the Trinity of Persons. Please don’t break my heart by praising me; but join me in praising God through Whom I have had my life. But it would mean a lot to me if you were to love me and to know that God sent me.” In many places in the Gospels, we notice how clearly Jesus, “the holy One of God”, understood this about Himself, as for example:

John 14 (NJB):

10 Do you not believe

that I am in the Father and the Father is in me?

What I say to you I do not speak of my own accord:

it is the Father, living in me, who is doing His works.

11 You must believe me when I say

that I am in the Father and the Father is in me;

or at least believe it on the evidence of these works.6

Therefore, St. Jerome would be relieved, and grateful, if you insisted that this painting is about other things than him. Could it be about the (divine) light that streams in from the left, illuminating his mind (notice how brightly his head/his intellect is shining), and which allows us to see this scene at all? Or could it be about those two Angels who have come to read along with him the Scriptures? (For heaven’s sake you couldn’t say the painting is about him when two beautiful Angels are right there!)

Notice how his Bible is open over there to his left, which stands under (i.e., “to understand”) the greatest Sign of his Lord, the Crucifix – the whole Scripture to be interpreted through the reality of that severe7 Beauty. Notice also how the Angels have laid open their Bible to the same pages, giving learned suggestions to St. Jerome as he works trying to decide how best to interpret a particular biblical passage.

5. ABOUT READING OF HOLY SCRIPTURE

1. It is for truth, not for literary excellence, that we go to Holy Scripture; every passage of it ought to be read in the light of that inspiration which produced it, with an eye to our souls’ profit, not to cleverness of argument. A simple book of devotion ought to be as welcome to you as any profound and learned treatise; what does it matter whether the man who wrote it was a man of great literary accomplishments? Do not be put off by his want of reputation; here is truth unadorned, to attract the reader. Your business is with what the man said, not with the man who said it.

2. Mankind is always changing; God’s truth stands for ever. And he has many ways of speaking to us, regardless of the human instruments he uses. Often enough, our reading of Holy Scripture is distracted by mere curiosity; we want to seize upon a point and argue about it, when we ought to be quietly passing on. You will get most out of it if you read it with humility, and simplicity, and faith, not concerned to make a name for yourself as a scholar. By all means ask questions but listen to what holy writers have to tell you; do not find fault with the hard sayings of antiquity—their authors had good reason for writing as they did.

1. It is for truth, not for literary excellence, that we go to Holy Scripture; every passage of it ought to be read in the light of that inspiration which produced it, with an eye to our souls’ profit, not to cleverness of argument. A simple book of devotion ought to be as welcome to you as any profound and learned treatise; what does it matter whether the man who wrote it was a man of great literary accomplishments? Do not be put off by his want of reputation; here is truth unadorned, to attract the reader. Your business is with what the man said, not with the man who said it.

2. Mankind is always changing; God’s truth stands for ever. And he has many ways of speaking to us, regardless of the human instruments he uses. Often enough, our reading of Holy Scripture is distracted by mere curiosity; we want to seize upon a point and argue about it, when we ought to be quietly passing on. You will get most out of it if you read it with humility, and simplicity, and faith, not concerned to make a name for yourself as a scholar. By all means ask questions but listen to what holy writers have to tell you; do not find fault with the hard sayings of antiquity—their authors had good reason for writing as they did.

CONVERSATION

Point One

Our author writes: “It is for truth, not for literary excellence, that we go to Holy Scripture; every passage of it ought to be read in the light of that inspiration which produced it, with an eye to our souls’ profit, not to cleverness of argument.”

Something that really bothered the younger St. Jerome about the Scriptures (and possibly the young, pre-Christian St. Augustine also), is that they were filled with examples of bad prose and poetry, of irritating repetitions, of inelegant writing, and regularly marked by unsophisticated thinking. For a man as learned and demanding as St. Jerome was, such sloppiness bothered him.

But then he had that “vision” or luminous moment in his life when Christ spoke directly to him, chidingly,8 that he had better get clear in himself whether he loved Cicero (the supreme literary stylist; philosopher; statesman of the Roman Republic) more than God. “It is for truth, not for literary excellence, that we go to Holy Scripture.”

Few people I know could be irritated with the Scriptures in the way that Jerome could, who have Jerome’s prodigious learning and commitment to excellence in study and thought and to a boldness of life in Christ, letting go of everything that would get in the way of that.

But I have met, often, Christians who at some level in their awareness feel irritated by, unsatisfied with, the way that the Bible or Theology is being taught to them. They notice a “thinness” of meaning given them; a kind of bored repeating of convictions by the teacher (sort of like watching a “fake” flame wiggle in the electric fireplace); a speaking about the Bible and of God in ways that seem suspiciously supportive of the world’s unredeemed way of thinking about things.

Our author writes: “It is for truth, not for literary excellence, that we go to Holy Scripture; every passage of it ought to be read in the light of that inspiration which produced it, with an eye to our souls’ profit, not to cleverness of argument.”

Something that really bothered the younger St. Jerome about the Scriptures (and possibly the young, pre-Christian St. Augustine also), is that they were filled with examples of bad prose and poetry, of irritating repetitions, of inelegant writing, and regularly marked by unsophisticated thinking. For a man as learned and demanding as St. Jerome was, such sloppiness bothered him.

Do not be put off by his [the biblical author’s] want of reputation; here is truth unadorned, to attract the reader. Your business is with what the man said, not with the man who said it.

But then he had that “vision” or luminous moment in his life when Christ spoke directly to him, chidingly,8 that he had better get clear in himself whether he loved Cicero (the supreme literary stylist; philosopher; statesman of the Roman Republic) more than God. “It is for truth, not for literary excellence, that we go to Holy Scripture.”

Few people I know could be irritated with the Scriptures in the way that Jerome could, who have Jerome’s prodigious learning and commitment to excellence in study and thought and to a boldness of life in Christ, letting go of everything that would get in the way of that.

But I have met, often, Christians who at some level in their awareness feel irritated by, unsatisfied with, the way that the Bible or Theology is being taught to them. They notice a “thinness” of meaning given them; a kind of bored repeating of convictions by the teacher (sort of like watching a “fake” flame wiggle in the electric fireplace); a speaking about the Bible and of God in ways that seem suspiciously supportive of the world’s unredeemed way of thinking about things.

2 Timothy 4 (NJB): 3 The time is sure to come when people will not accept sound teaching, but their ears will be itching for anything new, and they will collect themselves a whole series of teachers according to their own tastes; 4 and then they will shut their ears to the truth and will turn to myths.9

At some level, the Scriptures and the truth of God is no longer dangerous … as we intuit it should be.

The Oxford English Dictionary at “dangerous” – 2. – 1490 – Fraught with danger or risk; causing or occasioning danger; perilous, hazardous, risky, unsafe. (The current sense.)

Roger Dawson, SJ, “Dangerous Remembrance” in Thinking Faith by the British Province of Jesuits (11 November 2013):

Towards the end of the Second World War, a 16-year-old boy was conscripted into the German Army and was sent to the front near the Rhine in an infantry company of youths of a similar age. One evening, he was sent with a message to Battalion headquarters; he returned the next morning to find that his company of over a hundred had been overrun in the night by an Allied bomber attack and an armoured assault. He said, ‘I could see now only dead and empty faces, where the day before I had shared childhood fears and youthful laughter. I remember nothing but a wordless cry’. This man was Fr. Johann Baptist Metz (1928-2019),10 who later became a [Catholic] priest and one of the great 20th century theologians. He remained haunted by the memory and by this question: ‘What would happen if one took this not to the psychologist, but into the Church … and if one would not allow oneself to be talked out of such memories even by theology?’ What if we wanted to keep faith with such memories – dangerous memories, he calls them – and with them to speak about God?

Fr. Metz has provocatively said: “The shortest definition of Religion: interruption.” He also wrote: “The lightning bolt of danger lights up the whole biblical landscape, especially the New Testament scene.”11

Point Two

Our author writes: “And God has many ways of speaking to us, regardless of the human instruments he uses.”

There is no question among Christians of any stripe that we consider the Scriptures a privileged source of revelation by God in history, about God in history and beyond history. But “God has many ways of speaking to us” –

A Christian, above all others, should know that “God has many ways of speaking to us”, and that it is not only in the Bible. We must be seekers of all the ways that God speaks into our history – including in our neighbor … and in our enemy - both in the past and in our present, so that, frankly, we can read and understand our Scriptures more sufficiently. The Bible is replete13 with “many ways” that God chose to speak to our Ancestors. We need to notice that. And then there are the writings of the saints, of the mystics, of the theologians, of the philosophers, of the scientists, of the poets and novelists, of the artists – they all are replete in this way … but we have to learn how to recognize God there. Jesus meant this when he said:

Point Two

Our author writes: “And God has many ways of speaking to us, regardless of the human instruments he uses.”

There is no question among Christians of any stripe that we consider the Scriptures a privileged source of revelation by God in history, about God in history and beyond history. But “God has many ways of speaking to us” –

Dei Verbum – the Dogmatic Constitution on Divine Revelation of the Vatican Council II, published by the Council and Pope Paul VI on 18 November 196512 - In His goodness and wisdom God chose to reveal Himself and to make known to us the hidden purpose of His will (see Eph. 1:9) by which through Christ, the Word made flesh, man might in the Holy Spirit have access to the Father and come to share in the divine nature (see Eph. 2:18; 2 Peter 1:4). Through this revelation, therefore, the invisible God (see Col. 1;15, 1 Tim. 1:17) out of the abundance of His love speaks to men as friends (see Ex. 33:11; John 15:14-15) and lives among them (see Bar. 3:38), so that He may invite and take them into fellowship with Himself. This plan of revelation is realized by deeds and words having an inner unity: the deeds wrought by God in the history of salvation manifest and confirm the teaching and realities signified by the words, while the words proclaim the deeds and clarify the mystery contained in them. By this revelation then, the deepest truth about God and the salvation of man shines out for our sake in Christ, who is both the mediator and the fullness of all revelation. (my emphasis)

A Christian, above all others, should know that “God has many ways of speaking to us”, and that it is not only in the Bible. We must be seekers of all the ways that God speaks into our history – including in our neighbor … and in our enemy - both in the past and in our present, so that, frankly, we can read and understand our Scriptures more sufficiently. The Bible is replete13 with “many ways” that God chose to speak to our Ancestors. We need to notice that. And then there are the writings of the saints, of the mystics, of the theologians, of the philosophers, of the scientists, of the poets and novelists, of the artists – they all are replete in this way … but we have to learn how to recognize God there. Jesus meant this when he said:

John 10 (NJB):

14 I am the good shepherd;

I know my own

and my own know me,

15 just as the Father knows me

and I know the Father;

and I lay down my life for my sheep.

16 And there are other sheep I have

that are not of this fold,

and I must lead these too.

They too will listen to my voice,

that are not of this fold,

and I must lead these too.

They too will listen to my voice,

and there will be only one flock,

one shepherd.14

Point Three

Our author writes: “By all means ask questions but listen to what holy writers have to tell you; do not find fault with the hard sayings of antiquity—their authors had good reason for writing as they did.”

A key development in the maturing of our intellect happens when we begin to have the strength to endure not knowing, not (yet) understanding, but by this growing strength in us refusing to give up on trying to understand.

When I taught high school students, this was something that I needed them to recognize as important – the significance of the known unknown! That is, we know that what we seek still eludes us … but we know that it is there. This insight lies at the heart of the transition from Arithmetic to Algebra,15 when one has learned to name what he or she does not yet know – “Let X be…” – so that he or she may aim at X and then recognize that he or she knows it when he or she does!

It is no disrespect to question (faithfully, never unfaithfully) the Scriptures or Theology!16 What is disrespectful is not to question, not to make demands on ourselves to grow in our faithful understanding of God’s presence to us in the words and deeds of human beings of the great Traditions and currently, and in the Divine presence giving itself in the revelatory splendor of the natural world.

Our author writes: “By all means ask questions but listen to what holy writers have to tell you; do not find fault with the hard sayings of antiquity—their authors had good reason for writing as they did.”

A key development in the maturing of our intellect happens when we begin to have the strength to endure not knowing, not (yet) understanding, but by this growing strength in us refusing to give up on trying to understand.

When I taught high school students, this was something that I needed them to recognize as important – the significance of the known unknown! That is, we know that what we seek still eludes us … but we know that it is there. This insight lies at the heart of the transition from Arithmetic to Algebra,15 when one has learned to name what he or she does not yet know – “Let X be…” – so that he or she may aim at X and then recognize that he or she knows it when he or she does!

It is no disrespect to question (faithfully, never unfaithfully) the Scriptures or Theology!16 What is disrespectful is not to question, not to make demands on ourselves to grow in our faithful understanding of God’s presence to us in the words and deeds of human beings of the great Traditions and currently, and in the Divine presence giving itself in the revelatory splendor of the natural world.

Notes

1 To study or zoom-in on the painting: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:St.-Jerome-In-His-Study.jpg

2 Grove Art Online (Oxford): Cavarozzi [del Crescenzi], Bartolomeo - Italian painter, active also in Spain. … A more significant influence was that of the art of Caravaggio. Between 1610 and 1617 both Cavarozzi and Giovanni Battista Crescenzi became interested in this, and between 1615 and 1617, while still in Rome, Cavarozzi may have become acquainted with the Genoese painter Domenico Fiasella, who was also moving towards a Caravaggesque style. In any case, Cavarozzi was certainly a convert to Caravaggism by the time he left for Madrid in 1617, accompanying Giovanni Battista in the retinue of Cardinal Antonio Zapata Cisneros. … But the first true expression of Caravaggism in the work of Cavarozzi may have been in the St Jerome and Two Angels (Florence, Gal. Palatina). Raking light from the left illuminates the figures and picks out of the darkness the naturalistically rendered objects, among them a skull resting on tattered parchment pages and a book opened to an etching by Dürer. The attention to these details hints at a northern or Spanish link. Although influenced by Caravaggism, Cavarozzi retained aspects of his own style. He adopted the tenebrism of Caravaggio and peopled his canvases with substantial, naturalistic figures, but avoided the active drama present in the works of many of the Caravaggisti. Rather, his subjects appear to be graceful, high-born creatures imbued with gentle, restrained and even pensive natures. … Cavarozzi found few followers for his lyrical, intimate brand of Caravaggism. His importance for art history lies in his role as a conveyor of Italian Caravaggism to Spain, where the style influenced artists such as Murillo and Zurbarán.

2 Grove Art Online (Oxford): Cavarozzi [del Crescenzi], Bartolomeo - Italian painter, active also in Spain. … A more significant influence was that of the art of Caravaggio. Between 1610 and 1617 both Cavarozzi and Giovanni Battista Crescenzi became interested in this, and between 1615 and 1617, while still in Rome, Cavarozzi may have become acquainted with the Genoese painter Domenico Fiasella, who was also moving towards a Caravaggesque style. In any case, Cavarozzi was certainly a convert to Caravaggism by the time he left for Madrid in 1617, accompanying Giovanni Battista in the retinue of Cardinal Antonio Zapata Cisneros. … But the first true expression of Caravaggism in the work of Cavarozzi may have been in the St Jerome and Two Angels (Florence, Gal. Palatina). Raking light from the left illuminates the figures and picks out of the darkness the naturalistically rendered objects, among them a skull resting on tattered parchment pages and a book opened to an etching by Dürer. The attention to these details hints at a northern or Spanish link. Although influenced by Caravaggism, Cavarozzi retained aspects of his own style. He adopted the tenebrism of Caravaggio and peopled his canvases with substantial, naturalistic figures, but avoided the active drama present in the works of many of the Caravaggisti. Rather, his subjects appear to be graceful, high-born creatures imbued with gentle, restrained and even pensive natures. … Cavarozzi found few followers for his lyrical, intimate brand of Caravaggism. His importance for art history lies in his role as a conveyor of Italian Caravaggism to Spain, where the style influenced artists such as Murillo and Zurbarán.

3 The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church, 4th edition - St. Jerome (345-420 CE), biblical scholar and ascetic. Jerome studied at Rome, where he was baptized, and then travelled in Gaul before devoting himself to an ascetic life with friends at Aquileia. About 374 CE, he set out for Palestine. He delayed in Antioch, where he heard the lectures of Apollinarius of Laodicea until self-accused in a dream of preferring pagan literature to religious (Ciceronianus es, non Christianus – “You are a Ciceronian, not a Christian”). He then settled as a hermit at Chalcis in the Syrian desert for four or five years, and while there learnt Hebrew. … After [Pope] Damasus’ death he visited Antioch, Egypt, and Palestine, and in 386 CE finally settled at Bethlehem, where he ruled a newly founded men's monastery and devoted the rest of his life to study. Jerome's writings issued from a scholarship unsurpassed in the early Church. His greatest achievement was his translation of most of the Bible into Latin from the original tongues, to which he had been originally prompted by [Pope] Damasus (see the Vulgate translation). He also wrote many biblical commentaries, in which he brought a wide range of linguistic and topographical material to bear on the interpretation of the sacred text.

4 The Oxford English Dictionary at “subject” – III.12.a. - That which forms or is chosen as the matter of thought, consideration, or inquiry; a topic, theme. III.12.a.i. – 1563.

5 “Doctor of the Church” – Britannica: In Roman Catholicism, any of the 37 saints whose doctrinal writings have special authority. The writings and teachings of the various doctors of the church are of particular importance to Roman Catholic theology, and their works are considered to be both true and timeless. Although the title is not used in the same way in Eastern Orthodoxy, the Orthodox church esteems the 17 doctors of the church who died before the East-West Schism of 1045 CE, and Saints John Chrysostom, Basil the Great, and Gregory of Nazianzus are especially honored as the Three Holy Hierarchs.

4 The Oxford English Dictionary at “subject” – III.12.a. - That which forms or is chosen as the matter of thought, consideration, or inquiry; a topic, theme. III.12.a.i. – 1563.

5 “Doctor of the Church” – Britannica: In Roman Catholicism, any of the 37 saints whose doctrinal writings have special authority. The writings and teachings of the various doctors of the church are of particular importance to Roman Catholic theology, and their works are considered to be both true and timeless. Although the title is not used in the same way in Eastern Orthodoxy, the Orthodox church esteems the 17 doctors of the church who died before the East-West Schism of 1045 CE, and Saints John Chrysostom, Basil the Great, and Gregory of Nazianzus are especially honored as the Three Holy Hierarchs.

6 The New Jerusalem Bible (New York; London; Toronto; Sydney; Auckland: Doubleday, 1990), Jn 14:10–11.

7 The Oxford English Dictionary at “severe” – “not leaning to tenderness or laxity; unsparing.”

8 The Oxford English Dictionary “to chide” – 1.c. – 1393 – To scold by way of rebuke or reproof; in later usage, often merely, to utter rebuke.

7 The Oxford English Dictionary at “severe” – “not leaning to tenderness or laxity; unsparing.”

8 The Oxford English Dictionary “to chide” – 1.c. – 1393 – To scold by way of rebuke or reproof; in later usage, often merely, to utter rebuke.

9 The New Jerusalem Bible (New York; London; Toronto; Sydney; Auckland: Doubleday, 1990), 2 Ti 4:3–4.

10 See: https://johannbaptistmetz.com. Born in Germany in the 1920s, Johann Baptist Metz is among the most influential Catholic theologians of our time. As Professor of Fundamental Theology at the University of Münster until 1993 he introduced a brand of theology that speaks to the threatened future of humankind with a biblically sharpened view of the world.

11 In a memorial published (3 December 2019, America magazine) by an American scholar of the theology of Johann Baptist Metz, Matthew Ashley, wrote: “If Dietrich Bonhoeffer warned against the dangers of cheap grace, perhaps Metz will be remembered for his prophetic warnings against cheap hope: the thin hopes of a consumer culture that, Metz complained, has even abandoned its secular heritage from the Enlightenment of hoping for freedom, equality and fraternity for all humankind.”

10 See: https://johannbaptistmetz.com. Born in Germany in the 1920s, Johann Baptist Metz is among the most influential Catholic theologians of our time. As Professor of Fundamental Theology at the University of Münster until 1993 he introduced a brand of theology that speaks to the threatened future of humankind with a biblically sharpened view of the world.

11 In a memorial published (3 December 2019, America magazine) by an American scholar of the theology of Johann Baptist Metz, Matthew Ashley, wrote: “If Dietrich Bonhoeffer warned against the dangers of cheap grace, perhaps Metz will be remembered for his prophetic warnings against cheap hope: the thin hopes of a consumer culture that, Metz complained, has even abandoned its secular heritage from the Enlightenment of hoping for freedom, equality and fraternity for all humankind.”

12 This document is of the most important statements ever written on how Christians can sufficiently understand divine revelation. For the whole text: https://www.vatican.va/archive/hist_councils/ii_vatican_council/documents/vat-ii_const_19651118_dei-verbum_en.html.

13 “replete” – The Oxford English Dictionary at “replete” – 1.a. - c1384 – Abundantly supplied or provided with something (material or immaterial).

14 The New Jerusalem Bible (New York; London; Toronto; Sydney; Auckland: Doubleday, 1990), Jn 10:14–16.

15 I dread making any such assertion, because I know how significantly undeveloped I have always been at Mathematics!

16 The justifiably esteemed ALPHA endeavor, born among some gifted teachers at Holy Trinity Brompton in London, boasts about how completely it encourages ALPHA searchers not to ask the questions that they are supposed to ask but to ask the questions that they actually have, the answers to which they really need to discover.

13 “replete” – The Oxford English Dictionary at “replete” – 1.a. - c1384 – Abundantly supplied or provided with something (material or immaterial).

14 The New Jerusalem Bible (New York; London; Toronto; Sydney; Auckland: Doubleday, 1990), Jn 10:14–16.

15 I dread making any such assertion, because I know how significantly undeveloped I have always been at Mathematics!

16 The justifiably esteemed ALPHA endeavor, born among some gifted teachers at Holy Trinity Brompton in London, boasts about how completely it encourages ALPHA searchers not to ask the questions that they are supposed to ask but to ask the questions that they actually have, the answers to which they really need to discover.

Recent

Categories

Tags

Archive

2025

January

March

June

2024

January

March

September

October

2023

March

November

2022

2021

2020

2019

2018

1 Comment

“It is for truth, not for literary excellence, that we go to Holy Scripture; every passage of it ought to be read in the light of that inspiration which produced it, with an eye to our souls’ profit, not to cleverness of argument.”

n

nThere are passages in the Bible that seem unnecessarily repetitive or inefficient (in terms of word choice), but the aforementioned quote reminds us to focus on content. Each scriptural author had his own style, (which does not have to be our style), and sometimes there is meaning in overt prolixity. I make a habit of reading genealogies and repeated phrases in Numbers and Leviticus, for example, as part of my "religious practice."

n

nRegarding your notes, my home church was Holy Trinity Brompton when I lived in London as a teenager. Beautiful!