#7 - Conversations

#7 - Conversations

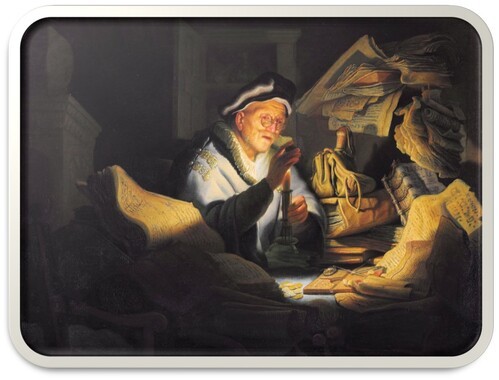

THE PAINTING

Luke 12 (NJB): 20 But God said to him, “Fool! This very night the demand will be made for your soul; and this hoard of yours, whose will it be then?” 21 So it is when someone stores up treasure for himself instead of becoming rich in the sight of God.’3

Let us look at the painting.

First, we notice the painter’s use of the chiaroscuro style/technique.

Grove Art Online (Oxford) at “chiaroscuro” – Term from the Italian compound of chiaro (‘light’, ‘clear’) and scuro (‘dark’) used to refer to the distribution of light and dark tones with which the painter, engraver or draughtsman imitates light and shadow; by extension it refers to the variations in light and shade on sculpture and architecture resulting from illumination.

I playfully imagine that Rembrandt, when facing an empty off-white canvas, decided to paint the entire surface black. “Why would he wreck his canvas in that way?” But then we see him picking up that special brush, the one kept apart in a beautifully crafted wooden box, the one that allows him to paint not with paints but with light itself. With that brush in his hand, a special gift from the Divine realm, we watch Rembrandt, stroke by deft stroke, begin to release from the darkness all that is hidden in it.

Genesis 3 (NJB): 9 But Yahweh God called to the man. ‘Where are you?’ he asked. 10 ‘I heard the sound of you in the garden,’ he replied. ‘I was afraid because I was naked, so I hid.’4

When the darkness is comprehensive, we not only cannot see what is hidden, but we do not even know that something is there!

John 1 (NJB):

9 The Word was the real light

that gives light to everyone;

he was coming into the world.

10 He was in the world

that had come into being through him,

and the world did not recognise him.5

Christ is our light, who sent to us the Holy Spirit, the real Artist of the bunch. She offers us Her gifts (inspiration; the gift of languages; brushes; musical instruments; the genius6 to compose poems and essays and novels, symphonies, paintings, buildings, etc.) so that we too might bring to light that which is hidden, as God began to do in that first moment of Creation:

Genesis 1 (NJB): In the beginning God created heaven and earth. 2 Now the earth was a formless void, there was darkness over the deep, with a divine wind sweeping over the waters. 3 God said, ‘Let there be light,’ and there was light [chiaro]. 4 God saw that light was good, and God divided light from darkness [scuro]. 5 God called light ‘day’, and darkness he called ‘night’. Evening came and morning came: the first day. 7

Second, we wonder whether that man wanted to be seen – whom the parable in Luke 12 has called “a rich fool” (because that is what Jesus called him). Did Rembrandt ask his permission? But how could Rembrandt have asked that, when he did not know that this man was there in the dark, surrounded by his wealth, until the light allowed Rembrandt to see him? Why should we be concerned whether Rembrandt has asked? Because that man, for all his prosperity, is revealed by that special brush to be painfully vulnerable, worried, unsure of himself … and all alone.

Look at that face! It is not a cruel face. But there is sadness and anxiety in it, and it shows the pinched ravages of Avarice.8

If all of those who had envied him for his apparently unceasing prosperity could see him as the light reveals him to be, then they might be grateful for his example, showing them another truth. Such prosperity is not what they had assumed it was: a stay against fear, against insecurity, against sadness, a sure way to secure the unwavering praise of others.

That remarkable face, and because of Rembrandt’s compassionate heart, teaches all of us exactly what Jesus meant by His warning expressed in Luke 12:16-21. But we do well prayerfully to ask God to let us hear how He said the following line, with what intonation and with what kind of emotion:

We assume an angry edge in God’s voice – “Fool!” And when we do assume this, we make a mistake, proving that we are thralls10 to Envy, unable to see what God sees, and how God sees this man, and to what end, and with holy patience and compassion.

There is not a shred of envy in Rembrandt as he wields his brush. Just look at the depth of feeling Rembrandt finds in the unveiled face of that man, all his self-conceit effaced.12

Rembrandt paints the moment when the divine light has shown him who he has become, what he has loved more than was healthy for him. He is trapped. (Do you see how he is trying to hoard13 the light, so that we cannot see it, keeping it all for himself?)

Rembrandt allows us to approach the man, as he tries to accept the unsettling truth of who he has become. We say, “We are here with you; we know. Do not fear this truth, because it is the holy Light that reveals it to you.”

The Oxford English Dictionary at the noun “worry” – 1.a. – 1804 – A troubled state of mind arising from the frets and cares of life; harassing anxiety or solicitude. But then at the verb “to worry”, from which the noun derives: 3.a. – 1340 – transitive. To seize by the throat with the teeth and tear or lacerate; to kill or injure by biting and shaking. Said e.g. of dogs or wolves attacking sheep, or of hounds when they seize their quarry.

If all of those who had envied him for his apparently unceasing prosperity could see him as the light reveals him to be, then they might be grateful for his example, showing them another truth. Such prosperity is not what they had assumed it was: a stay against fear, against insecurity, against sadness, a sure way to secure the unwavering praise of others.

That remarkable face, and because of Rembrandt’s compassionate heart, teaches all of us exactly what Jesus meant by His warning expressed in Luke 12:16-21. But we do well prayerfully to ask God to let us hear how He said the following line, with what intonation and with what kind of emotion:

20 But God said to him, “Fool! This very night the demand will be made for your soul; and this hoard of yours, whose will it be then?”9

We assume an angry edge in God’s voice – “Fool!” And when we do assume this, we make a mistake, proving that we are thralls10 to Envy, unable to see what God sees, and how God sees this man, and to what end, and with holy patience and compassion.

Envy, rooted ordinarily in a radical difficulty in trusting that God loves one uniquely and personally, moves the self-doubting person to covet what others seem to be or have. There is sadness or displeasure at the spiritual or temporal good of another. For many people, envy threatens if an atmosphere of competitiveness and comparison degenerates into an environment of stifling jealousy. Then the good of another becomes an evil to oneself, because it seems to lessen one’s own excellence. From envy can follow hatred and resentment, calumny and detraction. An individual plagued by envy usually needs to be helped to move toward a deeper sense of God’s love for him or her and to appropriate concern and compassion for others.11

There is not a shred of envy in Rembrandt as he wields his brush. Just look at the depth of feeling Rembrandt finds in the unveiled face of that man, all his self-conceit effaced.12

Rembrandt paints the moment when the divine light has shown him who he has become, what he has loved more than was healthy for him. He is trapped. (Do you see how he is trying to hoard13 the light, so that we cannot see it, keeping it all for himself?)

Rembrandt allows us to approach the man, as he tries to accept the unsettling truth of who he has become. We say, “We are here with you; we know. Do not fear this truth, because it is the holy Light that reveals it to you.”

George Herbert (1593-1633), “Love III” –

LOVE bade me welcome; yet my soul drew back,

Guilty of dust and sin.

But quick-eyed Love, observing me grow slack

From my first entrance in,

Drew nearer to me, sweetly questioning

If I lack’d anything.

‘A guest,’ I answer’d, ‘worthy to be here:’

Love said, ‘You shall be he.’

‘I, the unkind, ungrateful? Ah, my dear,

I cannot look on Thee.’

Love took my hand and smiling did reply,

‘Who made the eyes but I?’14

As my greatest spiritual teacher in this life, Fr. Gordon Moreland, SJ, once told me (but which remark took me years to understand), “Rick, we all want to be found out, though we also fear it. But the One who finds us is the One who loves us.”

7. ABOUT FALSE CONFIDENCE, AND HOW TO GET RID OF SELF-CONCEIT (De vana spe et elatione fugienda)

1. It is nonsense15 to depend for your happiness on your fellow men, or on created things. What does it matter if you have to be the servant of others, and pass for a poor man in the world’s eyes? It is nothing to be ashamed of, if you do it for the love of Jesus Christ. Why all this self-importance? Leave everything to God, and he will make the most of your good intentions. Put no confidence in the knowledge you have acquired, or in the skill of any human counsellor; rely on God’s grace—he brings aid to the humble, and only humiliation to the self-confident.

2. Do not boast of riches, if you happen to possess them, nor about the important friends you have; boast rather of God’s friendship—he can give us all we want, and longs to give us something more, himself. Do not give yourself airs if you have physical strength or beauty; it only takes a spell of illness to waste the one or mar the other. Do not be self-satisfied about your own skill or cleverness; God is hard to satisfy, and it is from him they come, all these gifts of nature.

3. He reads our thoughts, and he will only think the worse of you, if you think yourself better than other people. Even your good actions must not be a source of pride to you; his judgements are not the same as man’s judgements, and what commends you to your fellows is not, often enough, the sort of thing which commends you to him. If you have any good qualities to shew for yourself, credit your neighbour with better qualities still; that is the way to keep humble. No harm, if you think of all the world as your betters; what does do a great deal of harm is to compare yourself favourably to a single living soul. To be humble is to enjoy undisturbed peace of mind, while the proud heart is swept by gusts of envy and resentment.16

1. It is nonsense15 to depend for your happiness on your fellow men, or on created things. What does it matter if you have to be the servant of others, and pass for a poor man in the world’s eyes? It is nothing to be ashamed of, if you do it for the love of Jesus Christ. Why all this self-importance? Leave everything to God, and he will make the most of your good intentions. Put no confidence in the knowledge you have acquired, or in the skill of any human counsellor; rely on God’s grace—he brings aid to the humble, and only humiliation to the self-confident.

2. Do not boast of riches, if you happen to possess them, nor about the important friends you have; boast rather of God’s friendship—he can give us all we want, and longs to give us something more, himself. Do not give yourself airs if you have physical strength or beauty; it only takes a spell of illness to waste the one or mar the other. Do not be self-satisfied about your own skill or cleverness; God is hard to satisfy, and it is from him they come, all these gifts of nature.

3. He reads our thoughts, and he will only think the worse of you, if you think yourself better than other people. Even your good actions must not be a source of pride to you; his judgements are not the same as man’s judgements, and what commends you to your fellows is not, often enough, the sort of thing which commends you to him. If you have any good qualities to shew for yourself, credit your neighbour with better qualities still; that is the way to keep humble. No harm, if you think of all the world as your betters; what does do a great deal of harm is to compare yourself favourably to a single living soul. To be humble is to enjoy undisturbed peace of mind, while the proud heart is swept by gusts of envy and resentment.16

CONVERSATION

Point One

Our author writes: “Rely on God’s grace—he brings aid to the humble, and only humiliation to the self-confident.”

God has no interest, at all, in humiliating us. It is the evil spirit (“the enemy of our human nature” as St. Ignatius of Loyola calls Satan) who humiliates us, the most powerful form of which is shame.17

So, what could our author mean by “God’s grace brings … humiliation”? What he means is that God will expose our false self, if we let Him do it, revealing it for the cheat that it is, for the self-deception that it is. Rembrandt hopes that the man in the painting will let God do this. “Please, let God do this for you.”

It is the false self that feels humiliation at being found out, not the true self. It is the true self that in the dying of a false self knows that help has come to it and, upon experiencing this divine help, it cries out in such words as these, such words of which spiritual literature is filled:

Our author writes: “Rely on God’s grace—he brings aid to the humble, and only humiliation to the self-confident.”

God has no interest, at all, in humiliating us. It is the evil spirit (“the enemy of our human nature” as St. Ignatius of Loyola calls Satan) who humiliates us, the most powerful form of which is shame.17

So, what could our author mean by “God’s grace brings … humiliation”? What he means is that God will expose our false self, if we let Him do it, revealing it for the cheat that it is, for the self-deception that it is. Rembrandt hopes that the man in the painting will let God do this. “Please, let God do this for you.”

It is the false self that feels humiliation at being found out, not the true self. It is the true self that in the dying of a false self knows that help has come to it and, upon experiencing this divine help, it cries out in such words as these, such words of which spiritual literature is filled:

Amazing grace (how sweet the sound)

that saved a wretch like me!

I once was lost, but now am found,

was blind, but now I see.

Twas grace that taught my heart to fear,

and grace my fears relieved;

how precious did that grace appear

the hour I first believed!

Point Two

Our author writes: “Boast rather of God’s friendship.”

The “higher up” one ascends the social ladder, the more difficult it is for a person of stature to allow friendship with him or her, persons before whom he or she can be vulnerable. He or she thinks that this is a problem with other people. And the friends they allow are drawn from an increasingly smaller group of those whom he or she considers of equal “station” or “class” or “net worth” (such an astonishing and revealing expression).

What our author teaches, and this is meant for every one of us, is that when our primary friendship is with God (whose very existence is a relationship of love among the divine Persons – the source of all true friendship) the range and type of friendships we establish dramatically expands. The “higher up” one ascends into familiarity with God, the more people of all kinds and classes and capabilities feel our loving friendship toward them, with them, and in whose company he or she receives so much that is valuable to learn.

Now that is something worth “boasting” about, as often St. Paul did: closeness with God that makes our capacity for love more universal, not exclusive (the meaning of the Greek adjective “catholic”18), and a unifying and generous force in the world.

We Americans used to take seriously how we were: e pluribus unum; that is, “from the many, one.” Such an ideal, and any chance that it has to become a defining principle of a people, comes only by the grace of God, because only God knows how to be good at the world. Let’s admit it: we are not good at the world ... but in grace we can be.

Our author writes: “Boast rather of God’s friendship.”

The “higher up” one ascends the social ladder, the more difficult it is for a person of stature to allow friendship with him or her, persons before whom he or she can be vulnerable. He or she thinks that this is a problem with other people. And the friends they allow are drawn from an increasingly smaller group of those whom he or she considers of equal “station” or “class” or “net worth” (such an astonishing and revealing expression).

What our author teaches, and this is meant for every one of us, is that when our primary friendship is with God (whose very existence is a relationship of love among the divine Persons – the source of all true friendship) the range and type of friendships we establish dramatically expands. The “higher up” one ascends into familiarity with God, the more people of all kinds and classes and capabilities feel our loving friendship toward them, with them, and in whose company he or she receives so much that is valuable to learn.

Now that is something worth “boasting” about, as often St. Paul did: closeness with God that makes our capacity for love more universal, not exclusive (the meaning of the Greek adjective “catholic”18), and a unifying and generous force in the world.

We Americans used to take seriously how we were: e pluribus unum; that is, “from the many, one.” Such an ideal, and any chance that it has to become a defining principle of a people, comes only by the grace of God, because only God knows how to be good at the world. Let’s admit it: we are not good at the world ... but in grace we can be.

1 Corinthians 13 (NJB): 4 Love is always patient and kind; love is never jealous; love is not boastful or conceited, 5 it is never rude and never seeks its own advantage, it does not take offence or store up grievances. 6 Love does not rejoice at wrongdoing but finds its joy in the truth. 7 It is always ready to make allowances, to trust, to hope and to endure whatever comes. 8 Love never comes to an end.19

Point Three

Our author writes: “And what commends you to your fellows is not, often enough, the sort of thing which commends you to Him [to God].”

This comment again concerns the false self, its self-conceit, and how we manufacture the false self (and very often without noticing that we are doing it) to be a self that is pleasing to the world, and especially to the “important” people whose praise we seek. We might be consoled when contemplating the words of the beautiful hymn, “Be Thou My Vision” (written in Gaelic by Eleanor H. Hull, 1860-1935), one of whose stanzas reads:

4. Riches I heed not, nor vain, empty praise;

Thou mine inheritance, now and always.

Thou and thou only, first in my heart,

High King of Heaven, my treasure thou art.

Notes

1 To zoom in on the file see: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Rembrandt_-_The_Parable_of_the_Rich_Fool.jpg.

2 Grove Art Online (Oxford) at “Rembrandt” - Another painting dated 1626, the Musical Company (since 1976 in Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum.; Br. 632), is a mysterious scene previously thought to represent a musical party in Rembrandt’s house; it is more probably an allegory, though it has not been satisfactorily explained. The variegated colour scheme is still in Lastman’s style, while the still-life of books in the foreground must have been inspired by the vanitas pieces that were so much in vogue in Leiden in the 1620s. A striking feature is the concentrated fall of light, which became characteristic of Rembrandt’s work from then onwards. In his Leiden years he also painted a number of historical genre pieces or allegories. The Moneychanger (Berlin, Gemäldegal.; Br. 420) represents the Parable of the Rich Man (Luke 12:21), while the Sleeping Old Man (1629; Turin, Gal. Sabauda; Br. 428) is probably an allegorical depiction of Sloth. The Painter in his Studio (Boston, Mus. F.A.; Br. 419; see fig. below) symbolizes the working of the mind (ingenium) before the artist executes his work: true art was considered to be the result of ingenium, doctrina (the rules of art) and exercitatio (correct execution).

2 Grove Art Online (Oxford) at “Rembrandt” - Another painting dated 1626, the Musical Company (since 1976 in Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum.; Br. 632), is a mysterious scene previously thought to represent a musical party in Rembrandt’s house; it is more probably an allegory, though it has not been satisfactorily explained. The variegated colour scheme is still in Lastman’s style, while the still-life of books in the foreground must have been inspired by the vanitas pieces that were so much in vogue in Leiden in the 1620s. A striking feature is the concentrated fall of light, which became characteristic of Rembrandt’s work from then onwards. In his Leiden years he also painted a number of historical genre pieces or allegories. The Moneychanger (Berlin, Gemäldegal.; Br. 420) represents the Parable of the Rich Man (Luke 12:21), while the Sleeping Old Man (1629; Turin, Gal. Sabauda; Br. 428) is probably an allegorical depiction of Sloth. The Painter in his Studio (Boston, Mus. F.A.; Br. 419; see fig. below) symbolizes the working of the mind (ingenium) before the artist executes his work: true art was considered to be the result of ingenium, doctrina (the rules of art) and exercitatio (correct execution).

3 The New Jerusalem Bible (New York; London; Toronto; Sydney; Auckland: Doubleday, 1990), Lk 12:20–21.

4 The New Jerusalem Bible (New York; London; Toronto; Sydney; Auckland: Doubleday, 1990), Ge 3:9–10.

5 The New Jerusalem Bible (New York; London; Toronto; Sydney; Auckland: Doubleday, 1990), Jn 1:9–10.

6 The Oxford English Dictionary at “genius” – I. - A supernatural being, and related senses – 1. I.1.a. - a1387 – With reference to classical pagan belief: the tutelary god or attendant spirit allotted to every person at birth to govern his or her fortunes and determine personal character, and finally to conduct him or her out of the world. Also: a guardian spirit similarly associated with a place, institution, thing, etc.

7 The New Jerusalem Bible (New York; London; Toronto; Sydney; Auckland: Doubleday, 1990), Ge 1:1–5.

4 The New Jerusalem Bible (New York; London; Toronto; Sydney; Auckland: Doubleday, 1990), Ge 3:9–10.

5 The New Jerusalem Bible (New York; London; Toronto; Sydney; Auckland: Doubleday, 1990), Jn 1:9–10.

6 The Oxford English Dictionary at “genius” – I. - A supernatural being, and related senses – 1. I.1.a. - a1387 – With reference to classical pagan belief: the tutelary god or attendant spirit allotted to every person at birth to govern his or her fortunes and determine personal character, and finally to conduct him or her out of the world. Also: a guardian spirit similarly associated with a place, institution, thing, etc.

7 The New Jerusalem Bible (New York; London; Toronto; Sydney; Auckland: Doubleday, 1990), Ge 1:1–5.

8 “avarice” – One of the “deadly” or “capital” sins. “The theme of the deadly sins is featured prominently among a few of the most widely read writers of the Christian spiritual tradition. For example, Walter Hilton (d. 1396), in The Scale of Perfection, stresses love as the way of conquering strong enemies of humanity, the deadly sins. In directives to devout Christians faced with their own distorted self-love, Hilton analyzes each capital sin and describes the seven through various metaphors: streams running from the river of self-love, parts of the body of the devilish beast, separate evil animals. [Michael Downey, in The New Dictionary of Catholic Spirituality (Collegeville, MN: Liturgical Press, 2000), 249.]

9 The New Jerusalem Bible (New York; London; Toronto; Sydney; Auckland: Doubleday, 1990), Lk 12:20.

9 The New Jerusalem Bible (New York; London; Toronto; Sydney; Auckland: Doubleday, 1990), Lk 12:20.

10 “thralls” – The Oxford English Dictionary at “thrall” – I.1.b. - Old English – figurative. One who is in bondage to some power or influence; a slave (to something).

11 Michael Downey, in The New Dictionary of Catholic Spirituality (Collegeville, MN: Liturgical Press, 2000), 249–250.

12 “effaced” – The Oxford English Dictionary at “efface” – 1.a. – 1611 – To rub out, obliterate (writing, painted or sculptured figures, a mark or stain) from the surface of anything, so as to leave no distinct traces.

13 The Oxford English Dictionary at the verb “hoard” - 1.a. - Old English – transitive. To amass and put away (anything valuable) for preservation, security, or future use; to treasure up: esp. money or wealth.

11 Michael Downey, in The New Dictionary of Catholic Spirituality (Collegeville, MN: Liturgical Press, 2000), 249–250.

12 “effaced” – The Oxford English Dictionary at “efface” – 1.a. – 1611 – To rub out, obliterate (writing, painted or sculptured figures, a mark or stain) from the surface of anything, so as to leave no distinct traces.

13 The Oxford English Dictionary at the verb “hoard” - 1.a. - Old English – transitive. To amass and put away (anything valuable) for preservation, security, or future use; to treasure up: esp. money or wealth.

14 For the whole poem, see: https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/44367/love-iii.

15 “nonsense” – The Oxford English Dictionary at “nonsense” – I.1.b. – 1678 – Foolish or extravagant conduct; silliness, misbehaviour.

16 Kempis, Thomas à. The Imitation of Christ: Translated by Ronald Knox and Michael Oakley (pp. 31-32). Kindle Edition.

17 “shame” – Shaming is never directed at an ignoble, unworthy, sinful action. No. Shaming is directed at a person’s existence; it strikes at a person, at his or her right to exist at all. Shame is the at the very center of what Satan is and does.

18 “catholic” - καθολικός, A. general, universal. … c. as extending throughout the world, teaching the fullness of Christian doctrine, disciplining all classes of mankind, curing all kinds of sin and possessing every virtue [G. W. H. Lampe, ed., “Καθολικός,” in A Patristic Greek Lexicon (Oxford: At the Clarendon Press, 1961), 690.]

19 The New Jerusalem Bible (New York; London; Toronto; Sydney; Auckland: Doubleday, 1990), 1 Co 13:4–8.

15 “nonsense” – The Oxford English Dictionary at “nonsense” – I.1.b. – 1678 – Foolish or extravagant conduct; silliness, misbehaviour.

16 Kempis, Thomas à. The Imitation of Christ: Translated by Ronald Knox and Michael Oakley (pp. 31-32). Kindle Edition.

17 “shame” – Shaming is never directed at an ignoble, unworthy, sinful action. No. Shaming is directed at a person’s existence; it strikes at a person, at his or her right to exist at all. Shame is the at the very center of what Satan is and does.

18 “catholic” - καθολικός, A. general, universal. … c. as extending throughout the world, teaching the fullness of Christian doctrine, disciplining all classes of mankind, curing all kinds of sin and possessing every virtue [G. W. H. Lampe, ed., “Καθολικός,” in A Patristic Greek Lexicon (Oxford: At the Clarendon Press, 1961), 690.]

19 The New Jerusalem Bible (New York; London; Toronto; Sydney; Auckland: Doubleday, 1990), 1 Co 13:4–8.

Recent

Categories

Tags

Archive

2026

January

2025

January

March

June

October

2024

January

March

September

October

2023

March

November

2022

2021

2020

2019

No Comments