Advent Meditation 2025, Week 2

Advent Meditation, Second Week of Advent 2025

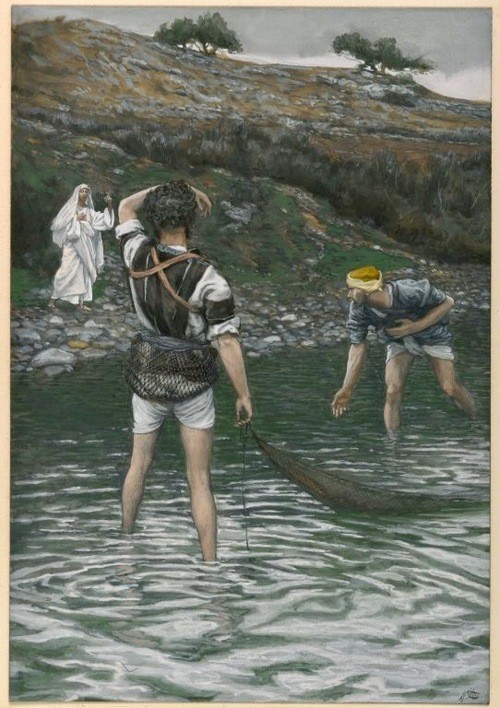

James Tissot (1836-1902), The Calling of Saint Peter and Saint Andrew (1886-1894)1, referencing Mark 1:16-18, housed in the Brooklyn Museum of Art.

Notice how the painter puts us in the same position as those two brothers, out in the shallow water looking back toward Jesus on the shore. Is Jesus, therefore, calling us too? Or, we wonder, had those two brothers been “calling” for God to show Himself to them for a long time, crying out to Him underneath the words of even the best prayers that they knew how to pray?

Romans 8 (NJB): 26 And as well as this, the Spirit too comes to help us in our weakness, for, when we do not know how to pray properly, then the Spirit personally makes our petitions for us in groans that cannot be put into words; 27 and he who can see into all hearts knows what the Spirit means because the prayers that the Spirit makes for God’s holy people are always in accordance with the mind of God.2

NOTE: For the best copy of this Meditation, with all formatting in place, click here for the PDF:

The Biblical Text Behind the Text (below)

John 14:5-6 (NJB):

William Barclay (1975) – Again and again Jesus had told his disciples where he was going, but somehow, they had never understood. “Yet a little while I am with you,” he said, “and then I go to him that sent me” (John 7:33). He had told them that he was going to the Father who had sent him, and with whom he was one, but they still did not understand what was going on. Even less did they understand the way by which Jesus was going, for that way was the Cross. At this moment the disciples were bewildered men. There was one among them who could never say that he understood what he did not understand, and that was Thomas. He was far too honest and far too much in earnest to be satisfied with any vague pious expressions. Thomas had to be sure. So, he expressed his doubts and his failure to understand, and the wonderful thing is that it was the question of a doubting man which provoked one of the greatest things Jesus ever said. No one need be ashamed of his doubts; for it is amazingly and blessedly true that he who seeks will in the end find. Jesus said to Thomas: “I am the Way, the Truth and the Life.” That is a great saying to us, but it would be still greater to a Jew who heard it for the first time. In it Jesus took three of the great basic conceptions of Jewish religion and made the tremendous claim that in him all three found their full realization.4

John 14:5-6 (NJB):

5 Thomas said, ‘Lord, we do not know where you are going, so how can we know the way?’ 6 Jesus said:

I am the Way; I am Truth and Life.

No one can come to the Father except through me.3

William Barclay (1975) – Again and again Jesus had told his disciples where he was going, but somehow, they had never understood. “Yet a little while I am with you,” he said, “and then I go to him that sent me” (John 7:33). He had told them that he was going to the Father who had sent him, and with whom he was one, but they still did not understand what was going on. Even less did they understand the way by which Jesus was going, for that way was the Cross. At this moment the disciples were bewildered men. There was one among them who could never say that he understood what he did not understand, and that was Thomas. He was far too honest and far too much in earnest to be satisfied with any vague pious expressions. Thomas had to be sure. So, he expressed his doubts and his failure to understand, and the wonderful thing is that it was the question of a doubting man which provoked one of the greatest things Jesus ever said. No one need be ashamed of his doubts; for it is amazingly and blessedly true that he who seeks will in the end find. Jesus said to Thomas: “I am the Way, the Truth and the Life.” That is a great saying to us, but it would be still greater to a Jew who heard it for the first time. In it Jesus took three of the great basic conceptions of Jewish religion and made the tremendous claim that in him all three found their full realization.4

Some Musical Versions of the Following Text

See: Northern Sinfonia with Director, Richard Hickox - Hickox Conducts Vaughan Wiliams (released 2000), “Five Mystical Songs: The Call”; Michael Leighton Jones and the Choir of Trinity College at the University of Melbourne (released 2008), Mystical Songs: Choral Music of Vaughan Williams, “Five Mystical Songs 4 – The Call”.

Text

“The Call” by George Herbert (1593-1633)5

In his collection called A Priest to the Temple; or the Country Parson (1652)

Come, my Way, my Truth, my Life:

Such a Way, as gives us breath:

Such a Truth, as ends all strife:

And such a Life, as killeth death.

[5] Come, my Light, my Feast, my Strength:

Such a Light, as shows a feast:

Such a Feast, as mends in length:

Such a Strength, as makes his guest.

Come, my Joy, my Love, my Heart:

[10] Such a Joy, as none can move:

Such a Love, as none can part:

Such a Heart, as joys in love.6

See: Northern Sinfonia with Director, Richard Hickox - Hickox Conducts Vaughan Wiliams (released 2000), “Five Mystical Songs: The Call”; Michael Leighton Jones and the Choir of Trinity College at the University of Melbourne (released 2008), Mystical Songs: Choral Music of Vaughan Williams, “Five Mystical Songs 4 – The Call”.

Text

“The Call” by George Herbert (1593-1633)5

In his collection called A Priest to the Temple; or the Country Parson (1652)

Come, my Way, my Truth, my Life:

Such a Way, as gives us breath:

Such a Truth, as ends all strife:

And such a Life, as killeth death.

[5] Come, my Light, my Feast, my Strength:

Such a Light, as shows a feast:

Such a Feast, as mends in length:

Such a Strength, as makes his guest.

Come, my Joy, my Love, my Heart:

[10] Such a Joy, as none can move:

Such a Love, as none can part:

Such a Heart, as joys in love.6

A Close Reading of the Text

Come, my Way, my Truth, my Life – Each of the three stanzas begins with the same word – come - a verb in the Imperative mood (how we express a command).7 What is hidden is the complement that this intransitive verb requires. We must supply “Come to me”. In other words, “my Way, my Truth, my Life” are three of this poet’s favorite personal names for his Lord – the poem will include nine names, nine divine names for God.

But there is something more important happening here. These first three titles are ones that Jesus gave to Himself at the Last Supper (see John 14:5-6, citation given above). But Jesus did not say “I am your Way; I am your Truth and Life”. So, how has it happened that our poet has made those names his own – “my Way, my Truth, and my Life”? This subtle point about grammar captures something of great spiritual significance. The poet is no longer treating Jesus Christ as one object to know among many other objects (the mark of a young spirituality, one that needs to mature). He now knows Jesus Christ as subject; that is, he now knows Him from the inside, if you will, by thinking and acting like Him – the meaning of “the imitation of Christ”. This is what St. Paul means:

This likening of us to God is perhaps the greatest work of the Holy Spirit in a human being.9

Come, my Way, my Truth, my Life – Each of the three stanzas begins with the same word – come - a verb in the Imperative mood (how we express a command).7 What is hidden is the complement that this intransitive verb requires. We must supply “Come to me”. In other words, “my Way, my Truth, my Life” are three of this poet’s favorite personal names for his Lord – the poem will include nine names, nine divine names for God.

But there is something more important happening here. These first three titles are ones that Jesus gave to Himself at the Last Supper (see John 14:5-6, citation given above). But Jesus did not say “I am your Way; I am your Truth and Life”. So, how has it happened that our poet has made those names his own – “my Way, my Truth, and my Life”? This subtle point about grammar captures something of great spiritual significance. The poet is no longer treating Jesus Christ as one object to know among many other objects (the mark of a young spirituality, one that needs to mature). He now knows Jesus Christ as subject; that is, he now knows Him from the inside, if you will, by thinking and acting like Him – the meaning of “the imitation of Christ”. This is what St. Paul means:

1 Corinthians 2:16 (NJB) – 16 For: who has ever known the mind of the Lord? Who has ever been his adviser? But we are those who have the mind of Christ.8

This likening of us to God is perhaps the greatest work of the Holy Spirit in a human being.9

John 14:16-17 (NJB):

16 I shall ask the Father,

and he will give you another Paraclete

to be with you forever,

17 the Spirit of truth

whom the world can never accept

since it neither sees nor knows him;

but you know him,

because he is with you, he is in you. 10

But one other remark about that opening command, “Come.” We expected, given the title of this text, “The Call”, that it would be about God’s calling of the poet, God’s summoning of him, giving the poet his vocation, “Come, follow me.” Instead, his poem is an invocation. He is, if you will, giving God His vocation (!), calling on God to show His best self towards and with him, the poet.

He is summoning God to be present to him, deploying his nine favorite names of God, as if to make his prayer irresistible to God.

Concerning the structure of the poem - How orderly he is in this holy Summoning! Did you notice? Consider the first stanza:

The first line of each stanza gives God three names – in this case, Way, Truth, Life. Then each of the following lines of the stanza explains, in turn, a cherished aspect (“such a”) of each name. We are often surprised at something in each name that we had not considered.

For example, I would not have expected “Truth” to be that which “ends all strife”. Why? Because in this American moment lying is considered clever and necessary, proof of an “effective” use of (ungoverned) power – “It’s just how the world works”. We force “truth” to be what we say it is. In such a world as this, speaking the truth (what is real, whether it is convenient or not) enflames strife; it does not end strife.

Do you see? To read this poem, each line, can summon each of us to think about each of these nine divine names. And when we do, the poem opens its depths to us.

This orderly structure extends to the rhyming pattern, following the same pattern in all three stanzas. The last word of the first line rhymes with the last word of the third line; the last word of the second line with the last word of the fourth line. This rhyming relates the two words, deepening the meaning of each: “life” rhymed with “strife”; “breath” with “death”. We are brought deeper into our understanding by considering the relation of the two words.

Take time to “play” inside these stanzas and the individual lines. Experience how the poem gives so much more than we initially guessed it would.

The Oxford English Dictionary at “invocation” – 1.a. - c1384 – The action or an act of invoking or calling upon (God, a deity, etc.) in prayer or attestation; supplication, or an act or form of supplication, for aid or protection.

He is summoning God to be present to him, deploying his nine favorite names of God, as if to make his prayer irresistible to God.

Concerning the structure of the poem - How orderly he is in this holy Summoning! Did you notice? Consider the first stanza:

Come, my Way, my Truth, my Life:

Such a Way, as gives us breath:

Such a Truth, as ends all strife:

And such a Life, as killeth death.

The first line of each stanza gives God three names – in this case, Way, Truth, Life. Then each of the following lines of the stanza explains, in turn, a cherished aspect (“such a”) of each name. We are often surprised at something in each name that we had not considered.

For example, I would not have expected “Truth” to be that which “ends all strife”. Why? Because in this American moment lying is considered clever and necessary, proof of an “effective” use of (ungoverned) power – “It’s just how the world works”. We force “truth” to be what we say it is. In such a world as this, speaking the truth (what is real, whether it is convenient or not) enflames strife; it does not end strife.

Matthew 10 (NJB): 34 ‘Do not suppose that I have come to bring peace to the earth: it is not peace I have come to bring, but a sword.11

Do you see? To read this poem, each line, can summon each of us to think about each of these nine divine names. And when we do, the poem opens its depths to us.

This orderly structure extends to the rhyming pattern, following the same pattern in all three stanzas. The last word of the first line rhymes with the last word of the third line; the last word of the second line with the last word of the fourth line. This rhyming relates the two words, deepening the meaning of each: “life” rhymed with “strife”; “breath” with “death”. We are brought deeper into our understanding by considering the relation of the two words.

Take time to “play” inside these stanzas and the individual lines. Experience how the poem gives so much more than we initially guessed it would.

An Advent Prayer

From The Gift: Poems by Hafiz (1325-1390) translated by Daniel Ladinsky –

Even

After

All this time

The sun never says to the earth,

“You owe

Me.”

Look

What happens

With a love like that,

It lights the

Whole

Sky.

From The Gift: Poems by Hafiz (1325-1390) translated by Daniel Ladinsky –

Even

After

All this time

The sun never says to the earth,

“You owe

Me.”

Look

What happens

With a love like that,

It lights the

Whole

Sky.

Notes

1 See: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Brooklyn_Museum_-_The_Calling_of_Saint_Peter_and_Saint_Andrew_(Vocation_de_Saint_Pierre_et_Saint_André)_-_James_Tissot_-_overall.jpg

2 The New Jerusalem Bible (New York; London; Toronto; Sydney; Auckland: Doubleday, 1990), Ro 8:26–27.

3 The New Jerusalem Bible (New York; London; Toronto; Sydney; Auckland: Doubleday, 1990), Jn 14:5–6.https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Brooklyn_Museum_-_The_Calling_of_Saint_Peter_and_Saint_Andrew_(Vocation_de_Saint_Pierre_et_Saint_André)_-_James_Tissot_-_overall.jpg

2 The New Jerusalem Bible (New York; London; Toronto; Sydney; Auckland: Doubleday, 1990), Ro 8:26–27.

3 The New Jerusalem Bible (New York; London; Toronto; Sydney; Auckland: Doubleday, 1990), Jn 14:5–6.https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Brooklyn_Museum_-_The_Calling_of_Saint_Peter_and_Saint_Andrew_(Vocation_de_Saint_Pierre_et_Saint_André)_-_James_Tissot_-_overall.jpg

4 William Barclay, ed., The Gospel of John, vol. 2 of The Daily Study Bible Series (Philadelphia, PA: Westminster John Knox Press, 1975), 156–157.

5 Peter McCullough, “Herbert, George,” in The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church, ed. Andrew Louth (Oxford, United Kingdom; New York: Oxford University Press, 2022) 875. - Herbert, George (1593–1633) Poet and divine. Born at Montgomery, a younger brother of Edward Lord Herbert of Cherbury, he was educated at Westminster School and Trinity College, Cambridge, where his classical scholarship and musical ability (he played the lute and viol and sang) secured him a fellowship in 1614. He became public orator of the university in 1620, and his success seemed to mark him out for the career of a courtier. The death of James I, however, and the influence of his friend, Ferrar [Nicholas Faerrar (1592-1637), founder of Little Gidding], led him to study divinity, and in 1626 he was presented to a prebend in Huntingdonshire. In 1630 he was ordained priest and persuaded by Laud to accept the rectory of Fugglestone with Bemerton, near Salisbury, where in piety and humble devotion to duty he spent his last years. … Herbert was a man of deep religious conviction and remarkable poetic gifts, masterly in handling both metre and metaphor. The ‘conceits’ in his verse are, with very few exceptions, still acceptable thanks to their genuine aptness and wit. The good sense of his didactic poems, and esp. the poignancy of the more personal lyrics, continue to ring true and have proved irresistible to many outside as well as within the Christian faith.

6 George Herbert, The Country Parson, The Temple, ed. John N. Wall Jr. and Richard J. Payne, The Classics of Western Spirituality (New York; Mahwah, NJ: Paulist Press, 1981), 281.

5 Peter McCullough, “Herbert, George,” in The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church, ed. Andrew Louth (Oxford, United Kingdom; New York: Oxford University Press, 2022) 875. - Herbert, George (1593–1633) Poet and divine. Born at Montgomery, a younger brother of Edward Lord Herbert of Cherbury, he was educated at Westminster School and Trinity College, Cambridge, where his classical scholarship and musical ability (he played the lute and viol and sang) secured him a fellowship in 1614. He became public orator of the university in 1620, and his success seemed to mark him out for the career of a courtier. The death of James I, however, and the influence of his friend, Ferrar [Nicholas Faerrar (1592-1637), founder of Little Gidding], led him to study divinity, and in 1626 he was presented to a prebend in Huntingdonshire. In 1630 he was ordained priest and persuaded by Laud to accept the rectory of Fugglestone with Bemerton, near Salisbury, where in piety and humble devotion to duty he spent his last years. … Herbert was a man of deep religious conviction and remarkable poetic gifts, masterly in handling both metre and metaphor. The ‘conceits’ in his verse are, with very few exceptions, still acceptable thanks to their genuine aptness and wit. The good sense of his didactic poems, and esp. the poignancy of the more personal lyrics, continue to ring true and have proved irresistible to many outside as well as within the Christian faith.

6 George Herbert, The Country Parson, The Temple, ed. John N. Wall Jr. and Richard J. Payne, The Classics of Western Spirituality (New York; Mahwah, NJ: Paulist Press, 1981), 281.

7 The Oxford English Dictionary at the verb “come” – I.5. - intransitive. In imperative. - I.5.a. - Old English – With complement. Used both as an invitation to approach or join and as an invitation or encouragement to proceed with an action or activity performed alongside, or for the benefit of, the speaker.

8 The New Jerusalem Bible (New York; London; Toronto; Sydney; Auckland: Doubleday, 1990), 1 Co 2:16.

9 In the eastern half of the Christian Church – Greek or Orthodox Christianity, this likening is spoken of as deification – a centrally important theological idea for them. See Stephen Thomas at “Deification” in the Encyclopedia of Eastern Orthodox Christianity: “Deification” and sometimes “divinization” are English translations of expressions used by the church fathers to describe the manner in which God saves his elect by mercifully initiating them into his communion and his presence. The most-used Greek term, theōsis, acts as a master-concept in Greek theology, by which the truth of doctrinal statements is assessed. The fathers used theosis to bring out the high condition to which human beings are exalted by grace, even to the sharing of God’s life. Theosis means that, “In Christ,” we can live at the same level of existence as the divine Trinity, to some extent even in this life, and, without possibility of falling away in the next.”

8 The New Jerusalem Bible (New York; London; Toronto; Sydney; Auckland: Doubleday, 1990), 1 Co 2:16.

9 In the eastern half of the Christian Church – Greek or Orthodox Christianity, this likening is spoken of as deification – a centrally important theological idea for them. See Stephen Thomas at “Deification” in the Encyclopedia of Eastern Orthodox Christianity: “Deification” and sometimes “divinization” are English translations of expressions used by the church fathers to describe the manner in which God saves his elect by mercifully initiating them into his communion and his presence. The most-used Greek term, theōsis, acts as a master-concept in Greek theology, by which the truth of doctrinal statements is assessed. The fathers used theosis to bring out the high condition to which human beings are exalted by grace, even to the sharing of God’s life. Theosis means that, “In Christ,” we can live at the same level of existence as the divine Trinity, to some extent even in this life, and, without possibility of falling away in the next.”

Recent

Categories

Tags

Archive

2026

January

2025

January

March

June

October

2024

January

March

September

October

2023

March

November

2022

2021

2020

2019

No Comments